Oral History: Susan Milano

Susan Milano is a videomaker and co-founder of the Women’s Video Festival, a trailblazing event series that brought together art, activism, videomaking, and feminism. In this oral history, Milano discusses her introduction to video technology, her early videotapes, the origins of the festival, her involvement with a panoply of ‘70s art formations—including Global Village, The Kitchen, the Women’s Interart Center, and Shirley Clarke’s TP Videospace Troupe—and her career in Japanese television. This oral history was conducted in late 2020 and has been edited and expanded for clarity.

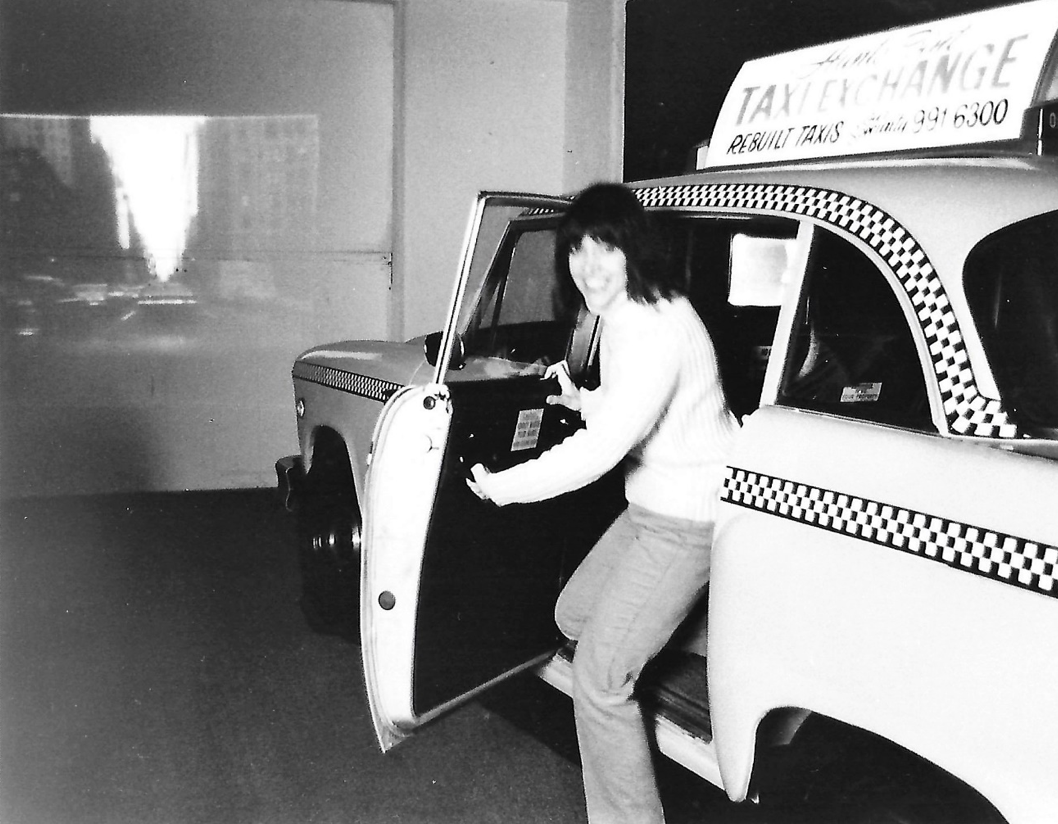

Susan Milano exiting Taxi, a video installation from the show “Back Seat,” produced in 1978 at the Women’s Interart Center. Photograph by Trix Rosen.

Tyler Maxin: How did you first get involved in video culture?

Susan Milano: Well, that’s really a story of transformation, given that I was raised in a convent boarding school for eight years beginning at the impressionable age of 5, and the video revolution was still decades away in the future. The options for young women like me at that time were limited. Marriage was the most significant goal, and until Mr. Right came along, a career as a teacher, nurse or secretary would do. As for higher education, in those years before the second wave of feminism, it was ‘common knowledge’ that college might be a good place to meet a husband. But I came from a family of musicians and because they were all performers, I always had it in my mind that I would wind up either singing or acting.

As a teen I’d been in a couple of plays at nearby Seton Hall, because the university didn’t admit women in those days and theatre club members would reach out to girls that they knew to come and audition when a production was being mounted. It was great fun and I became friendly with one of the guys in the club who used to get free tickets to all kinds of things in New York because he had a radio show on campus. John would take me to see foreign films, or to off-off-Broadway shows, and on a couple of occasions, we did photo shoots together with me as his subject. And after I was no longer involved with the club, we stayed in touch from time to time, but little did I know how significant this friendship would be.

Tyler Maxin: In what way?

Susan Milano as a “stage-struck teen,” circa mid-1960s. Photograph by John Reilly.

Flyer for a “smoke-in” at Tompkins Square Park, August 12, 1967. For larger view, click here.

Susan Milano: Well, it took a while. Although I was a little young for it, I was attracted to the Beat Generation, so after a brief stint at college, I left New Jersey and moved to the Lower East Side in New York. Suddenly I’m living in Allen Ginsberg’s neighborhood with poetry readings at St. Mark’s Church, and smoke-ins to make marijuana legal happening at Tompkins Square Park. The neighborhood, which was white, Puerto Rican, and Black, was a virtual melting pot of hippies, Beats, artists, writers, musicians, political activists, junkies, potheads, and kids like me. And no one had money.

During the day I worked as a clerk in the beautiful main branch of the Public Library, and at night I’d hang out with friends in the neighborhood or stop in at the notorious Annex Bar. As time went on, I moved further and further away from the traditional life that I led growing up…traveling cross-country by motorcycle with my boyfriend Ed Visitacion, two years before the cult film Easy Rider was released, just as the Beat Generation was fading out and hippies were coming to the forefront.

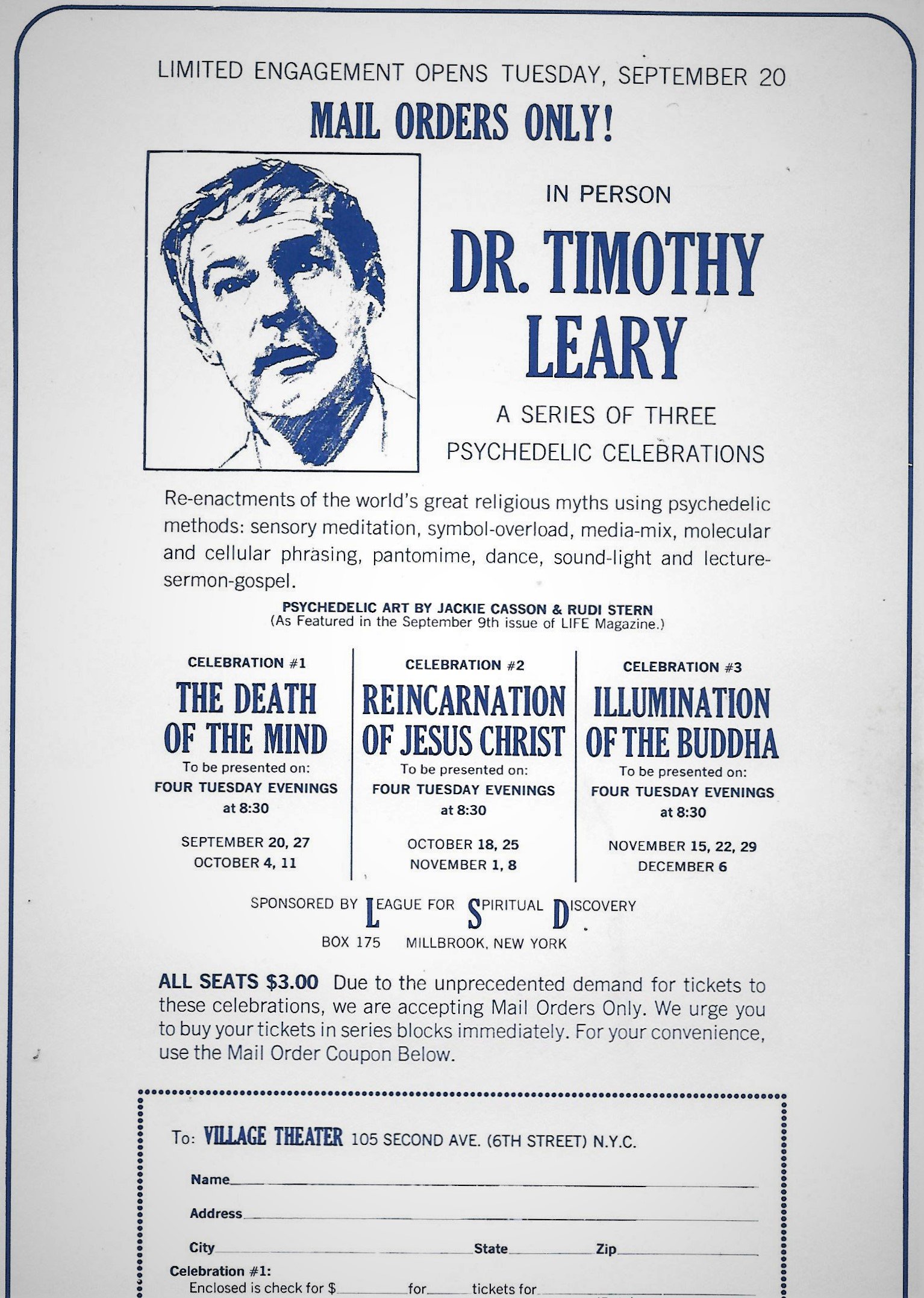

Handbill promoting Dr. Timothy Leary’s Psychedelic Celebrations, 1966. For larger view, click here.

The music scene played a prominent role in our lives and for a short period of time a group of us worked on a project to convert a neighborhood seltzer factory into a recording studio, as a pathway for local groups to be discovered as Motown had done. Throughout all of this, dropping acid and the “search for enlightenment” prevailed and influenced the way we dressed, the way we ate, and the people that we admired. That same early boyfriend and I even silk-screened prayer banners for Timothy Leary’s Psychedelic Celebrations at the the Village Theater (subsequently the Fillmore East). There was a lot going on and it was easy to get involved in all kinds of craziness, if you were so inclined.

Fast forward a bit and it’s now 1970. I’ve got an interesting day job working for the president of a small think tank whose mission is to discover and/or invent products that never existed before, and one day I’m looking through the entertainment section of The Village Voice and there’s an ad for something called Global Village. There was no description as to what this was, but my attention was drawn to a familiar name in the listing… John Reilly. Was this the same John Reilly I knew from Seton Hall?

I telephoned. It had been a while since we’d seen each other and in the interim he had co-founded what I would soon learn was one of the seminal groups working with this new electronic medium called video. I said, “what is this?” With no further description, he urged me to come over to SoHo on the weekend and see a show, although I had no idea what a show might be—a live performance, perhaps? “I think you’re gonna like it,” he said, accurately guessing that when I saw images of hippies and protesters come to life on a TV screen, I would be interested. That simply didn’t happen on commercial television.

Tyler Maxin: How was it that you finally became involved with Global Village?

Susan Milano: After seeing the first show, I’d gone back to Global a few times, and John kept trying to persuade me to quit my job and start hanging out there. Finally, one day he asked me to help him with a shoot he wanted to do with this journalist, A.J. Weberman, who was a self-described expert on Bob Dylan. At the time, Dylan had a house on MacDougall Street and because he had refused A.J.’s request for an interview, A.J. started stealing his garbage and then writing about it in The Village Voice. So we met up with A.J. only to discover that Dylan’s garbage can was empty. No problem, A.J. loaded it up with somebody else’s trash, John told me how to use the microphone and then shot this whole, funny interview with A.J. talking about what was in the can. Meanwhile, the housekeeper came out and began arguing that this was not Dylan’s garbage...blah blah blah, while I’m just lying on the sidewalk in the cold, taking sound for the whole thing.

I suddenly had an epiphany: “Wow, this is just such a bizarre situation. Here I am, outside Bob Dylan’s house. The family has stopped putting their garbage out because this guy has been stealing it and writing about it. This is for me!” A few days later I quit my job and joined Global Village.

Stills from John Reilly’s The Ballad of A.J. Weberman, 1969, produced by Global Village. Susan Milano can be seen holding a microphone as Weberman rummages through the household’s trash can.

The work is in the collection of Media Burn, a Chicago-based non-profit that collects, produces, and distributes documentary video created by artists, activists, and community groups, and can be viewed on their website.

Tyler Maxin: Could you describe what Global Village did on a day-to-day basis? What type of people were involved?

Susan Milano: At Global, John Reilly and Rudi Stern were the principals, and for the most part, they worked independently of each other, producing videotapes that would be shown at the weekend screenings, along with works from other early videomakers who were also shooting in half-inch, using portapaks.¹ Joie Davidow worked closely with Rudi, and I worked closely with John. He took me almost everywhere and that’s how I learned to use the gear, and how I met the Vasulkas at the very beginning. Subject matter knew no bounds, but clearly, counter-culture was dominant. We took half-inch to Washington D.C. to shoot some FCC proceedings. We snuck two portapaks into Carnegie Hall and covered a benefit that was sending money to Ireland because of The Troubles.² And as a group, Global did an all-day multi-screened show at the Eighth Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York produced by Charlotte Moorman in 1971, which is where Reilly introduced me to John Lennon.

As regards the type of people who were involved at Global Village, the short answer is, a wide array. There was a lot of interest in this new medium, and when I began working there, they were just starting the first of what became an ongoing series of workshops in video production through the New School. Between the times I accompanied John on his adventures, and his assigning me to the workshop, I got a lot of location experience because John relied on me to be with his student group from beginning to end.

Just to give a little primer, this video equipment that had been introduced by Sony was part of the first commercial iteration of what was regarded as “portable.” Weight of the recording deck was 19 pounds, and the camera was another seven. That’s laughable when you think of today, but compared to what existed at that time, it was “portable.” Networks had begun using video in their studios in the 1950s but the equipment was enormous, and the tape alone was two inches wide, whereas the width of tape for this portable format was just a half-inch. Consequently, when smaller systems were developed certain technical compromises had to be made and the net result was that anything recorded on half-inch video equipment did not meet the technical standards set by the government for commercial broadcast.

Sony’s “portapak” was intended for the consumer market and everything about it was fragile and ill-suited for the kind of “professional” approach that we were concerned with. Learning the vagaries of what could go wrong only happened with hands-on experience, and with a whole group of people going through this simultaneously, it was brutal on the equipment. By today’s standards half-inch video looks primitive and yet to achieve even that it took the ingenuity and persistence of individuals who devised all kinds of work-arounds to make up for the technical limitations at that time.

Tyler Maxin: When you entered the fray as a video maker in your own right, what were those early videos like?

Susan Milano: In Reilly’s New School class at Global Village we met once or twice a week and whenever shootings were arranged. He said we would use a documentary approach, and after much discussion we chose the subject of what was then referred to as “transsexualism,” which had been suggested by class member Daniel Landau. The Stonewall rebellion had happened just 18 months or so prior, and controversial topics of this nature were not usually within mainstream conversation. Landau was an openly gay man and had spoken about his own sexual orientation. He knew several key people who we could approach for potential interviews, so everyone agreed to go with his idea.

Flyer for the premiere screening of Transsexuals, 1971. A new, lightly restored digitization was shown via Chicago’s Media Burn in 2020. The film resource CINE–FILE noted: “As one of the earliest documentaries on the lives and experiences of transgender individuals, it’s a fascinating and valuable document both of the intimate possibilities of early video and of trans representation in media; it’s also moving in its simplicity and sincerity.”

Looking at the 1971 documentary Transsexuals today, its visual style and aesthetic seem rough and amateurish, but we established such a good rapport with our subjects that all these years later it has been recognized for its sensitivity and hailed for being one of the earliest histories documenting the transgender experience in an authentic way. During production, everyone was very eager to use the equipment, and we rotated crew positions for that reason. It was only when we got to post-production that attendance fell off. Around that time, Shridhar Bapat, a dropout from the London School of Economics who was also new to video, started hanging out at Global, and together he and I took on the job of editing.³ Occasionally a student might stop in to watch while we worked, the one exception to that being Elyshia Pass, who came multiple times throughout. It is noteworthy that one of our principal subjects, Deborah Hartin, subsequently became a prominent advocate on the issue of transgender identity. It was a surprise to learn, when I had the tape digitized a few years ago and could watch it again, that we actually captured a cameo appearance of a young Sylvia Rivera in 1971 demonstrating against the treatment of transgender people at The Tombs, a municipal jail in lower Manhattan, years before she became the icon that everyone came to know.⁴

Tyler Maxin: Can you speak in more detail about the content of Transsexuals?

Susan Milano: Certainly. When Daniel Landau brought the subject up for discussion most of the group knew very little about the topic. I remembered Christine Jorgensen, whose story had been highly publicized in the 1950s, but Daniel knew people in the present day who were more informed on this and he approached them about being videotaped.⁵ Ultimately, we focused on the stories of Deborah Hartin and Esther Reilly, both of whom had undergone gender-affirming surgery and who spoke in some detail about their lives.

With the help of an electrologist who treated many transgender individuals we were able to interview a diverse group of his clients, at a social gathering he put together. We covered an early demonstration for gay rights and did a street shooting soliciting “public opinion.” This was 1971 and one of the constants in much of the documentary work from Global Village featured street interviews.

Portrait of Jean Carroll, subject of Tattoo, date and photographer unknown. For larger view, click here.

Tattoo was a different story. It was in 1972 that I decided to leave Global Village and when I did I came into a tiny windfall and bought my own portapak. It sounds like I keep going back to the Dark Ages, but in 1972 tattooing had not yet captured the imagination of popular culture here. I became interested in it because my hair stylist, a gentle, mild-mannered young guy, had a tiny devil tatted on his arm, and he just didn’t fit the image of a drunk sailor or a macho he-man, which, in America anyway, was the stereotypical concept of people who got tattooed. Having my own portapak freed me up and I was inspired to seek out Jean Carroll, sometimes billed professionally as The Tattoo Queen, who I had seen several years before when she performed in Hubert’s Museum, a dime store circus on 42nd Street. I was off and running and completed the tape at the end of six months. Within a year or two, tattoos started showing up on all kinds of unlikely people and the rest is history.⁶

Tyler Maxin: How did the Women’s Video Festival get started?

Susan Milano: When the Vasulkas opened The Kitchen, word got around pretty quickly and they made it known that anyone who wanted to come and screen their work or put a show together could do so. They had been screening their own tapes and doing their own events, but there was no way that they could possibly fill programming 365 days a year. They’d done a Computer Arts Festival in spring of 1972, which I’d gone over to see, and after the event Steina and I went to have a drink together at Obie Alley, the bar in the Mercer Arts Center.⁷

She said, “You know, there are so many women who are in video using this equipment, and we hardly had any at all represented in the Computer Arts Festival. Would you be interested in doing a show of work by women?” and I said, “Sure.” I had been working on my Tattoo doc, but I was no longer spending my days at Global Village. Shridhar Bapat had already gotten involved at The Kitchen and we had worked together well and become friends when we were editing the Transsexuals tape. So I pulled in another friend, Laura Kassos, and together the three of us made it happen. It was just that casual. Steina and Woody went away for summer vacation, and while they were away, the three of us went to work. The show opened at summer’s end, in September.

Program from the first Women’s Video Festival, featuring illustrations by Rochelle Ohstrom (née Steiner), 1972. For larger view, click here.

Tyler Maxin: How did you source the videos for the first Women’s Video Festival?

Susan Milano: Primarily through word of mouth. Steina had put me in touch with Shigeko Kubota and I’d gone over to visit her and Nam June [Paik] when they were living at Westbeth. Other people I found through contacts within the video community, since we sometimes would come together at meetings about access to cable TV and things like that. Shridhar and I sent out letters and asked people to pass the word and before we knew it we received a flurry of responses!

At this point in time, there had been a lot of funding that was available from federal and private sources. Community groups all across the country had developed ideas for incorporating video into their social programs. And as a consequence, many people got access to portapaks and editing equipment locally and were finding a variety of ways to use this new medium. In a pre-internet time, there was also a plethora of small publications about how places were using video, and after word about the first Women’s Video Festival got out, many of the contacts we developed occurred because of these small periodicals. We didn’t just concentrate on arts organizations, but rather on almost any places that might be providing access to video.

Our invitation letter described the show as a festival of work by women. However, there was no limitation as to what the subject matter, or type of work could be…fiction, documentary, or fantasy. We didn't prohibit entries if men worked on them, but we were looking for material that was mainly driven by the ideas and the work of women. There wouldn’t be a jury; we would play anything we received. And that's what happened. The festival was to run for two weeks that first year but we received some late entries and added on a third week to accommodate them.

As for attendance, I was shocked in those opening days when I looked around and realized that the place was packed…and mostly with women. I thought, where did they all come from? I pretty much considered myself to be apolitical. I didn’t self-identify as a feminist and yet, I wasn’t against feminism either. I was simply involved with pursuing what interested me, but as a result of this experience it wasn’t long before I joined the team.

Some of the work was godawful; some of it was compelling. It was all over the map and when Steina asked me if I'd be interested in doing another festival the next year, I said yes. She introduced me to Howard Wise, who said, “Well, you’ll have to write up a grant proposal.” And that's how year number two got planned.

Tyler Maxin: Can you speak about the Festivals that followed?

Susan Milano: Sure. The second Women’s Video Festival was actually the show that opened the 1973 season when The Kitchen moved to the LoGiudice Gallery in SoHo after the Mercer Arts Center had collapsed and The Kitchen was forced to relocate. We followed the same format as the previous year, although Charlotte Moorman appeared, not on tape, but in a live performance, Crotch Music, which was a first. That year’s festival was also unforgettable to me for the night I unwittingly got into a war over volume levels with Stevie Wonder and his band, who happened to be playing for a private party upstairs from us in Joe LoGiudice’s loft. But I digress.

Images from the 1973 Women’s Video Festival at the LoGiudice Gallery. On the left Susan Milano and Shridhar Bapat tend to some equipment. For larger view, click here. Audience members on the right are waiting for Charlotte Moorman (not pictured here) to begin her performance. For larger view, click here. Photographs by Ann Volkes.

Tyler Maxin: What was the Women's Interart Center, and what was it like teaching video workshops there?

Susan Milano: The Women's Interart Center (“WIC” or “the Center”) began as an idea conceived by a group of female artists who in 1969 had been aggressively challenging art institutions about the lack of women’s work presented in museums, collections, and exhibitions.⁸ As their meetings about their activities became more frequent, they realized that they needed to have a home base and found a space on the top floor of a nearly empty industrial building in Hell's Kitchen on West 52nd Street one block from the river. I believe they were all painters, and they loved the light up there on the tenth floor and turned it into a gallery space, but the location was a far cry from the funky, fashionable place that is Hell’s Kitchen now. While the proximity to the river and a small park nearby seemed innocent enough on a summer day, at night the neighborhood was dark and forbidding and it was a long, lonely walk from the nearest subway, with punishing winds in winter and a sense of danger that was not for the faint of heart.

Their mission was to support female artists by providing services where they could study, collaborate, and present their work publicly, and members could enroll in workshops of their choosing for a very modest fee. As new courses were added, they rented more floors in the building to accommodate all that was going on. They redesigned the top floor so it could function as what would become an award-winning off-off-Broadway theatre as well as an adjacent gallery for visual arts and installations.

The range of things one could study was very diverse, and often reflected areas of interest that were in tune with what was currently hot. That’s how the video workshop started. Margot Lewitin, WIC’s Director, had come to the first Women’s Video Festival, and that’s how we met. I think she already knew that I had been teaching video at Global Village and asked if I was interested in teaching a workshop at the Center. I said yes. I knew nothing about them beforehand, and although they were there to support women in the arts, and they chose not to characterize WIC as a feminist organization, of course it was.

This was the first time I’d taught a women-only group and I came to appreciate this approach, particularly since we were dealing with technology. It never failed that in mixed gender workshops I’d given, when we’d come to the point of putting the gear in people’s hands, men would always rush forward, and women would hang back. It was as if our roles were culturally pre-determined by gender and I’d seen this happen many times. In the workshops at the Center, there was no hanging back, so for beginners, reaching the goals of getting comfortable with using the gear and gaining confidence came sooner.

Christine Noschese and Susan Milano at the Women’s Interart Center, checking out a portapak before a shoot, 1973. Photograph by Ann Volkes. For larger view, click here.

Betty Brown of the LOVE Tapes Collective, editing at the Center, circa mid-1970s. Photograph by Ann Volkes. For larger view, click here.

A monthly schedule of events for the Center, September 1974. Photograph by Jill Lynne. For larger view, click here.

Our first production, The Priest and The Pilot, (1973) focused on Helen Jost and Jeannette Piccard. Ms. Jost was among the small percentage of female aviators who held certification in both fixed wing and rotor craft and she was the first woman to operate a commercial power-line helicopter patrol service. Even today, only 7% of certificated pilots are women. Ms. Piccard, who had achieved some degree of fame and notoriety when she held the women’s altitude record for balloon flight for nearly three decades, and according to some accounts was regarded as the first woman in space, had realized in her later years that she had a religious calling and when we covered her story at age 78, was pursuing induction as an Anglican priest at a time when this simply was not possible.

Tyler Maxin: So starting with the third iteration of the festival, I imagine you might've had to jury it in some way? How else did the approach change, if at all?

Susan Milano: You’re right. There were many changes, and we did jury the third festival. The show was well-enough known by then and we were getting plenty of entries. And…it was time. We moved it to the Center after an uncomfortable financial dispute with the new director at The Kitchen, which was quietly resolved through the NY State Council on the Arts. I had been directing the video program at WIC and in December of ‘73, Margot Lewitin suggested that a group of us from the Center take (what would be) a weekend workshop with Shirley Clarke.

Shirley had a modern day salon going on in her Tower Playpen on the roof of the Chelsea Hotel and many artists, actors, celebrities and people of all stripes would come by and play. She had been experimenting with half-inch tape recording gear for a while and had little interest in simply using it as a substitute for film, but rather explored how it might be used to exploit the characteristics that were peculiar to this new medium. It was the influence of that weekend we spent with Shirley Clarke that took all of us in a new direction.⁹

The video improvisation from What’s On Tonight, 1974. From L to R: Wendy Clarke, Susan Milano, Tracy Fitz, and Betty Brown, with Christine Noschese and Wendy Clarke on monitors. Photograph by Ann Volkes. For larger view, click here.

The TP Videospace Troupe on tour at SUNY Buffalo, 1974. From L to R: Andrew Gurian, Shirley Clarke and Susan Milano. Photographer unknown. For larger view, click here. Watch Milano discuss her involvement with the Troupe in this interview with Beth Capper.

No one was using video as process in the way that she was, and her approach was so compelling that when the new year came, her daughter Wendy (who had worked alongside Shirley for that marathon) continued working with our group, the result of which was a remarkable show of video sculptures, games and theatrical improv, called What’s On Tonight. It was presented at the Center in late spring 1974, and it was the first appearance of my sculptural piece The Video Swing. Soon after that Shirley invited me to become a member of the TP Videospace Troupe and I happily accepted.

Susan Milano on The Video Swing, installed in the 1975 Women’s Video Festival held at the Women’s Interart Center. Photograph by Daniel Hedges.

When the third Festival occurred, which wasn’t until April 1975, we (Ann Volkes and I, together as co-coordinators) expanded the range of work to include sculpture and environments. The gallery space at WIC featured two Video Toys created by Wendy Clarke. Daile Kaplan presented one piece from her “Real Time Series” entitled The Shower. And I re-mounted The Video Swing in a simpler, cleaner fashion than its first run.

Similarly, to present videotapes, we designed and built multiple viewing environments in the theatre space that were wired up with camera feeds going back and forth between all of them and us, using a switcher that was custom made for me by Videofreex member Chuck Kennedy. From a master control room Ann Volkes and I could create interplay in the viewing spaces, whether it be with videotapes or live camera images.

“Partners in crime” Ann Volkes and Susan Milano, 1975. Photograph by Trix Rosen.

Photos from the third Women’s Video Festival at the Women’s Interart Center, 1975. Left: the entryway. For larger view, click here. Right: the control room. For larger view, click here. Photographs by Daniel Hedges.

Tyler Maxin: What were the environments like?

Susan Milano: The viewing environments were built inside a circular structure that was sliced into three sections, like a pie, with walls of corrugated cardboard serving as separations. The simplest space was “The Pillow Room” where audience members could watch the show as they lay on top of a mound of large colorful pillows on a carpeted floor, beneath a wafting baby-blue parachute.

For people who wanted more conventional seating, there was the “Then and Now Room” where folding chairs were neatly set out in front of a bank of monitors, flanked by giant black and white photos on the walls with images of women from the early days of television, dressed as they were in the roles that they played such as, Lucille Ball from I Love Lucy, Dale Evans from The Roy Rogers Show, Mary Martin as Peter Pan, Ann Sothern from Private Secretary, Imogene Coca from Your Show of Shows, and several others.

But the most popular viewing space was the “Glitter Room“ where we built a raked floor (the back of the room was raised up higher than the front) and covered the entire thing in foam topped off with leopard print fabric. People left their shoes outside the entry and climbed in to watch the show, while lying beneath gold painted monitors hanging from above. It was a massive hit.

Installation images from the third Women’s Video Festival at the Women’s Interart Center, 1975. From top to bottom: “The Pillow Room,” “The Then and Now Room,” and “The Glitter Room.” Photographs by Daniel Hedges.

Susan Milano: The fourth and final Festival that originated out of New York City was in 1976, again at the Women’s Interart Center, with interactive environments, and video sculptures: Mary Lucier’s Antique With Video Ants And Generations of Dinosaurs; Maxi Cohen’s My Bubi My Zada… a visit with the folks…a living room experience; and Shigeko Kubota’s - Marcel Duchamp’s Grave.

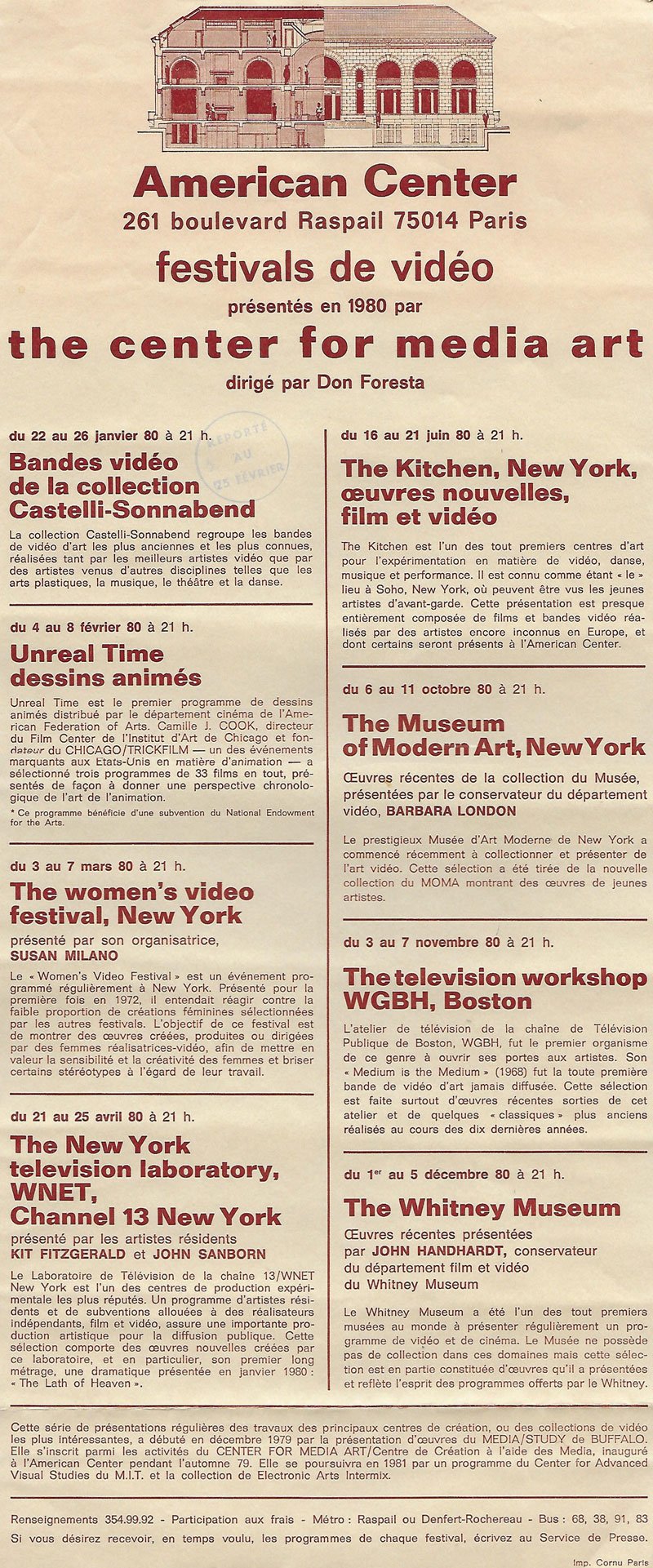

By the time the Festival ended that year, I was focused on further tours of work drawn from the shows, especially as I’d already successfully brought a sampler to SUNY Buffalo in 1975, and there was interest in doing a show at San Francisco State University later in 1976. Ultimately, I toured work from the Festival to the places in the list that follows, the last of which were in Paris and Belgium in 1980. Then a contemporary revitalization that is currently underway started at Hofstra University in 2017, when they hosted the renowned “Berkshire Conference on The History of Women, Genders and Sexualities.” I presented some of these early pieces to the amazement of an audience that was shocked to learn that this whole moment in women’s history had even occurred. Naturally their response spurred me on to continue my efforts to preserve, present and tell the story of that exciting time when the new technology of video and second-wave feminism traveled on parallel roads together.

Left: Poster for the American Center’s 1980 media art screening program which included a week dedicated to the Women’s Video Festival, as well as selections from other prestigious collections including the Castelli-Sonnabend and The Kitchen catalogues, The Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, and television stations WNET and WGBH. For larger view, click here. Above: the Women’s Video Festival on tour at SUNY Buffalo, 1975. Photograph by Joseph Hryvniak. For larger view, click here.

The traveling iterations of the Women’s Video Festival occurred between 1975 and 1980, as well as a more recent screening at an academic conference about Women’s History. The complete list is:

1975: SUNY Buffalo, New York (tapes and environments)

1976: San Francisco State University, California (tapes and environments)

1977 – Barnard College, New York (tapes only)

1978 – University of South Florida (tapes only)

1980 – American Cultural Center, Paris, France (tapes only)

1980 – Belgium – two theatre locations (tapes only)

2017 – Berkshire Conference on The History of Women, Genders and Sexualities, Hofstra University, New York (tapes only)

Tyler Maxin: So these touring shows, they were sort of like a taped compilation of works representative of the festival? What works would they usually include?

Susan Milano: The traveling shows were never identical, but I can give you a thumb-nail description of some of the pieces that were shown. Let It Be (Steina Vasulka, 1971) was one of her earliest short gems with her take on the Beatles’ hit of the same name. Tattoo (Susan Milano, 1972) was described as “a complex and compassionate portrait” of a woman’s transformation from a bearded lady in love into a fully tattooed “Queen.” The Rape Tape (Jenny Goldberg, 1972) was a series of personal confessions of the experiences of four women as each passed the camera from one to the next. There was Dressing Up (Susan Mogul, 1973), where the maker enters the scene in dishabille and illustrates how she has taken to heart her mother’s philosophy “Never buy anything full price” by telling us the provenance of every article of clothing as she gets dressed. Streets of Ulster (Louise Denver and David Redom, 1973) was a report on The Troubles in Northern Ireland where women and children were on the frontlines fighting British soldiers in the streets.

Harriet (Nancy Cain, 1973) was a tape about the diurnal monotony and secret fantasy life of a devoted mother, wife, and homemaker named Harriet. Fifty Wonderful Years (Miss California Pageant) (Optic Nerve, 1973) was a look behind the scenes [of this annual event] as this long-accepted tradition of exploiting women for their beauty was coming under fire. There was Women of Northside Fight Back (Christine Noschese, Marissa Gioffre, Valerie Bouvier, 1974), in which working-class women from Brooklyn who never imagined themselves as feminists effectively interjected their voices into a fight to save their neighborhood, and Snapshot: Florynce Kennedy (LOVE Tapes Collective, 1975), a recording of the Feminist Party founder speaking out at a Lesbian Feminist Liberation program in NYC. And there was Ama L’uomo Tuo (Always Love Your Man) (Cara DeVito, 1975), in which the maker’s 75-year-old grandmother tells of the conflict she encountered as she endured an abusive relationship with the man she married.

Tyler Maxin: You mentioned Video Swing and the influence of Shirley Clarke, and I know you made a number of other more environment-based pieces. Tell me a bit about how working in that expanded field affected your approach?

Susan Milano: During the seventies most of my work was spread out within the non-profit community, promoting other women vis à vis the festival, creating art of my own, writing proposals for funding, documenting role-play in the training of drug counselors, and teaching in a variety of venues. By 1977 I felt the need to refresh my batteries and just do something of my own. I got an idea for a show of video installations in automobiles and asked Videofreex members Nancy Cain and Bart Friedman if they’d like to work on it with me. That was the last production I presented at the Women’s Interart Center, and it was kind of an homage to American car culture.

“Back Seat” took place in 1978 and was composed of three pieces. Taxi was a nostalgic nod to the last generation of the Brooklyn cabbie, mounted in a yellow Checker with a collection of authentic homegrown New York cabbies whose heads appeared one at a time on a monitor placed just above the driver’s seat, as if they were at the wheel. ‘Passengers’ slid into the back seat and were regaled with tales about big tippers, celebrities, and taxi lore.

Drive-In was a love affair with that mid-century phenomenon which had all but disappeared from the American landscape, and it featured a 1950 Chevrolet parked in front of a screen showing coming attractions to East of Eden (1955) with James Dean, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) with Jimmy Stewart. Sound was transmitted from a drive-in speaker placed appropriately inside the front passenger side and a necking couple could be seen on a monitor facing out from the interior rear window.

The third piece, Country Road, took place in a small ceramic Volkswagen beetle, perhaps 10” in length and stripped of its roof. It sat upon a black draped pedestal and was positioned so the viewer could stand behind it and look through its tiny windshield to watch the scenery of a drive along a winding country road playing on a one-inch monitor.

The show was a great success and parts of it were subsequently recreated at venues in upstate New York where it was very well received. As you might imagine, since this involved actual vehicles, the pre-requisites at any given location were somewhat unique.

Nancy Cain, Bart Friedman, and Susan Milano, Drive In and Country Road, from the “Back Seat” show at the Women’s Interart Center, 1978. Photographs by Trix Rosen.

Tyler Maxin: A lot of people who were involved in the early days of video culture later got involved in other facets of the industry, yourself included. Could you talk a bit about your experience with other aspects of the video/television industry?

Susan Milano: In the meantime, I had already joined a small start-up that was one of the very first companies that provided location production services in small-format video. TV networks were still married to film but a lot of network producers wanted to use video and would persuade their bosses to hire us.

Backstage pass for “video staff” from Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band’s The River tour, Mesa Arizona, 1980.

I took on a variety of roles, as a producer, production manager, and assistant editor. I loved working with that team at Barry Rebo’s and stayed there for about six years. The chemistry of the original group was kind of magical and among many other things, we covered stories about Bruce Springsteen on The River tour, Muhammed Ali prepping for his 1980 fight with Larry Holmes, Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video (1979) for Lorne Michaels, and, in London, The Wall concerts for Pink Floyd. And then through someone I vaguely knew, I was introduced to the world of Japanese television in the early 1980s.

Tyler Maxin: Oh, interesting, describe that experience.

Susan Milano: Margie Smilow, a woman I’d met at one of my shows had lived in Japan in the early ‘70s, and while there, she fell in with some media people. At that time, the culture in Japan was such that when you got a job with a corporation, you pretty much stayed with that company for the rest of your life. You were a “salary man.” Anyway, she had been working with this group of people who had seceded from one of the major networks and started their own television production company, which was quite a revolutionary idea. These guys were young, they liked to travel and they loved coming to America. So they developed a concept for a show that would enable them to do that, not knowing that it would soon become the granddaddy of all game shows in Japan—and I would say, perhaps the precursor to reality TV—The Trans-America Ultra Quiz.

Tyler Maxin: As I understand it, that was a very significant piece of Japanese pop culture. It had a very large viewership.

Susan Milano: Yes. It was huge. It aired once a year in the fall, an eight-hour show that ran like a miniseries, two-hour episodes for four weeks in a row. It purported to offer the contestants who qualified a grand tour of iconographic sites in America for as long as they lasted in the competitions, which were staged at such locations along their journey from Tokyo to New York City, where the surviving winner would be crowned. Each two-hour episode would follow them through the succession of their travels where the quizzes had taken place chronicling who was still in the running, and who had failed and been sent home. The show became so popular that if you were the last one left standing, you’d be all over the front page of Japan’s newspapers the next morning.

Competition to get on the show was fierce and usually began on a publicly-announced day at an arena such as the Tokyo Dome. Thousands of people would gather on the field along with five or six mobile camera crews and the Master of Ceremonies, Norio Fukutomi, “the Johnny Carson of Japan,” who would ask a series of questions about America that had ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ answers. The competitors would run to one side of the stadium’s field to signal ‘Yes’… or to the other side to signal ‘No,’ as the mobile crews captured the resulting enthusiasm and confusion. This ingenious method enabled them to winnow the crowd down to perhaps 60 people or so within the space of a day. That would be Round One. The last year that I worked on the show 25,000 people had turned up for Round One.

Stills from The Trans-America Ultra Quiz VII, 1984. From top to bottom: the game begins in Tokyo; the “organized chaos” from the first day; the “running quiz” on location in Monument Valley. Photographs by TV Man Union.

As a production challenge it was unmatched by anything in my experience, either before or since. Part of the show’s success could be attributed to the elements of spectacle, danger, and endurance…whether that be in the choice of location, of things that would take place on location, or of physical and mental fortitude.

As a production manager one of the most important issues I dealt with was safety, whether there were performers setting themselves on fire, or if 25 pounds of honeybees were being poured over a contestant. Since our locations were often in remote areas and national parks, or as in the year when Ultra Quiz went “From the Top of the World to the Bottom of the World” and we were shooting in Barrow, Alaska, where I hired hunters to keep us safe from polar bears that might wander into town, everything had to go off without a hitch. There were no cell phones in those years and we had but one month to complete shooting all the locations which usually numbered about 15 or so. Our timetable for accomplishing what we needed left no room for error. None.

Stills from The Trans-America Ultra Quiz VII, 1984. Left: five final contestants compete at Niagara Falls; right: two contestants head home from Niagara Falls in barrels for the “penalty game.” Photographs by TV Man Union.

I worked on Ultra Quiz for 6 seasons during the 1980s, interrupted only in 1985, when I was hired by Louis Alvarez and Andrew Kolker to travel across America with them in search of “native” speakers with regional accents for what became their Peabody Award winning documentary, American Tongues, and which subsequently premiered as the first episode of the PBS series, “POV.” On these long overland journeys with only each other for company, I shared many stories about my experiences working on “UQ.”

The two of them became so amused, curious, and tickled by these tales that they eventually went to Japan and made a documentary entitled The Japanese Version, which they describe as “an unusual look at the West's influence on Japanese popular culture, from weddings with giant rubber cakes, to ‘love hotels’ decorated in different Western fantasies; to Tokyo businessmen in letter-perfect cowboy outfits singing the theme to Rawhide,” all of which were a natural fit for footage from Ultra Quiz XII in 1988.

That portion of The Japanese Version covers some of the play of the game at different locations around America, as well as “the botsu game”, a concept that would never fly in the U.S. Translated as “the penalty game” this was a tradition in Ultra Quiz which took place at the end of each round of play when a loser (or two) would be sent back home. Before leaving, he or she would have to first go through one more test for the camera. It might be something mildly humiliating, like going off to check in at the airport dressed in nothing more than a barrel (as was done once at Niagara Falls), or it might be something more elaborate, like being “trained” to be a professional card dealer and then assigned to a private party with threatening looking guests as was done in Las Vegas.

Susan Milano, as interviewed in Louis Alvarez and Andrew Kolker’s The Japanese Version (1991), a documentary on how Western cultural ideas and objects are reinterpreted in Japan. A segment of the documentary on Ultra Quiz is available to view on YouTube. For more information on Alvarez and Kolker’s documentaries, including institutional rentals, visit The Center for New American Media (CNAM)’s website.

To render an adequate description here of the breadth of this “game show” would be tantamount to the task of engraving the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin. Suffice to say that much of what I’ve seen online currently does not accurately portray the show as I knew it in the days leading up to 1990, and perhaps I’ll get to flesh out my memories of that time in a different forum. But to be criss-crossing through middle-America as it was in the 1980s with a cast and crew that at times numbered up to 60 Japanese-only speakers, when it was rare to even get a glimpse of the occasional Japanese tourist outside of New York or California, was an experience that has no match. Because of my adventures with Ultra Quiz I’ve now been to—or worked in—48 of the 50 states and it has provided me with a lifetime supply of stories to tell over cocktails.

Yuya Uchida swimming in the Hudson River in a promotional campaign for Parco, a department store, 1985.

When I decided to leave Ultra Quiz, I began getting requests from other Japanese producers and directors who, thankfully, assumed that if I could be successful on that show, I could be successful for them. This led to another decade of projects spanning perhaps eighty topics ranging from the idiotic (Is it possible to purchase land on Mars?) to the sublime (investigating the “true” story of the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911). The closest any of these projects came to involving danger was when I was hired to help guarantee the survival of a Japanese rock icon, Yuya Uchida, who was to swim in the Hudson River as part of an ad campaign for a major department store. He came through it alive and it was amusing to learn, many years later, that most people who saw the ad thought it had been done using green screen.

In between assignments from Japan, I had the occasional American job such as associate editor on the first cooperative television project between the U.S. and China, Big Bird in China (1983) (Children’s Television Workshop), and as a producer to the technical director on Fast Forward Into the Future, (1984) a major industrial project for Sony’s presentation at the annual Las Vegas trade show then called COMDEX. We introduced what I believe was the first commercial use of a wall of monitors in a scripted representation of the principle demonstrated by my Video Swing installation that had happened a decade earlier. In a way, I had come full circle.

Left: The Video Swing was covered by Dominique Belloir in the article Vidéo Art Explorations from a 1981 issue of Cahiers du Cinema, which also included a drawing of the piece. For larger view, click here. Right: Storyboard from the script of Fast Forward Into the Future, illustrating movement through multiple monitors in videospace, 1984. For larger view, click here.

While the move into the commercial field from my early involvement with video art and activism happened fairly easily, I never could have imagined that I would be lucky enough to have such interesting and even bizarre work over all this time. Perhaps that moment of epiphany on the A.J. Weberman shoot so many years ago was prescient. I have always been attracted to the “outside” or “otherness” of people and situations. I went with it then, and it rarely disappointed.

¹ The term portapak refers to a portable analog video recording system comprised of a video camera with a built-in microphone and electronic viewfinder (which functions as a small monitor for playback) that is designed to operate a battery-powered video tape recorder (VTR). In the vernacular, portapak referred to either the entire system, or solely the recording deck. Sony’s portapaks became the most popular, although other manufacturers such as Panasonic and Akai marketed their own versions. The origin of the word portapak is unclear; while it is strongly associated with Sony, the company did not use the term in the marketing for their product, the Video Rover. Variations of the term include “portapack” or “porta-pak,” and the indiscriminate use of an upper case “P” is sometimes applied to any or all versions. For the purposes of this conversation, the term has been standardized as “portapak.”

² The Troubles were an ethno-nationalist conflict between the overwhelmingly Protestant unionists and Roman Catholic nationalists. Though Ireland was granted independence from Britain in 1921 after the Easter uprising in 1916, the six counties of Northern Ireland remain under British control today. This deal has triggered intermittent unrest, peaking in 1968 through 1998 when the Catholics of Ulster actively fought against British rule and the Unionist government. This period was documented in a number of noteworthy videos including Louise Denver and David Redom’s The Streets of Ulster (1973) and John Reilly and Stefan Moore’s The Irish Tapes (1975), one of the first major video documentaries produced with 1/2-inch portable equipment, a version of which is viewable via Media Burn.

³ For more on Shridhar Bapat’s life and work, as an early participant in The Kitchen and the downtown video arts scene, see Keefe, Alexander, “Aleph Null” originally published in Bidoun, issue 27: Diaspora, summer 2012. Available online here.

⁴ After successfully undergoing a gender affirming surgery by a doctor in Casablanca in 1970, a time when little was known or understood about this topic, Deborah Hartin (1933-2005) became the first person to obtain an updated birth certificate from the state of New York reflective of her name, although without any indication of her gender. It wasn’t until 2016 that New York finally allowed individuals to change both name and gender on birth certificates. See more at Zagria, “Deborah Hartin (1933-2005), Sailor, Activist,” A Gender Variance Who’s Who, 2016, viewable online here. See also, a state-by-state overview of of changing gender on birth certificates here. Sylvia Rivera (1951-2002), famously associated with the Stonewall rebellion of 1969 and a founding member of the Gay Liberation Front, was a co-founder (along with Marsha P. Johnson) of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). An extensive obituary is available from the International Foundation for Gender Education.

⁵ Christine Jorgensen (1926-1989) was one of the earliest transgender individuals whose story became public in the United States. In 1950 she went to Denmark where a doctor who had been experimenting in gender therapy was instrumental in helping to develop a comprehensive plan using hormonal therapy, and surgery. Upon returning from Denmark she became a national sensation and went on to develop a successful career as an actress and performer. For more on this history and others, see the Digital Transgender Archive.

⁶ For more on Jean Carroll, see Osterud, Amelia Klem, Jean Carroll – The Tattooed Lady, A History (Speck Press, 2009). Carroll died a few months after the production of Milano’s Tattoo. Hubert’s Museum, where Carroll often performed in later life, was often considered the last of the Times Square dime-store museums or flea circuses that offered cheap, lowbrow entertainment. Hubert’s—a frequent haunt of photographer Diane Arbus, who photographed many of the performers—went out of business in 1965, although some exhibitions remained open until 1969. For more information, see The New York Times, The Flea Circus of Times Square.

⁷ The Mercer Arts Center was a complex of small, off-off-Broadway theaters in Greenwich Village that had been carved out of the back side of the formerly grand Broadway Central Hotel in late 1971. Steina and Woody Vasulka secured the last available space as a venue for the burgeoning electronic art scene, naming it “The Kitchen” as a nod to its former purpose when the original hotel was at its zenith during the Gilded Age and frequently hosted grand banquets. In August 1973, the building abruptly collapsed. The Kitchen’s equipment was spared and it relocated to a new space in SoHo.

⁸ The Women’s Interart Center was registered as a nonprofit corporation in New York State in October 1971 to “encourage and advance the development and expression of women’s skills and creativity in all areas of the arts.” The Center’s output during its 47 year run (1969-2016) was prolific: It presented over 800 events in the performing, media, and visual arts, garnering ten Obies and many other awards. At its peak, hundreds of artists a year took part in its training courses, workshops, and productions. While the organization’s administration during much of that time leaned toward a non-hierarchical structure with a Board of Directors, Margot Lewitin served as the overall Director beginning around 1972-73 until it closed. The Center’s extensive archive of nearly half a century of papers and ephemera documenting its history has been acquired by the New York Public Library and is gradually becoming available in the Performing Arts division located at Lincoln Center.

⁹ Filmmaker and video artist Shirley Clarke lived in a pyramid-shaped tower on the roof of the Chelsea Hotel, which served as her home and studio space. Clarke and her cohort often referred to the space as the “TeePee” or “TP” (standing for “Tower Playpen”), inspiring the name of her TP Videospace Troupe, a loose collective working in experimental film and video. For further reading, see Gurian, Andrew, “Thoughts on Shirley Clarke and the TP Videospace Troupe,” Millennium Film Journal #42, fall 2004. For Milano’s reflections on her participation in the troupe, see Capper, Beth, “Interview with Susan Milano,” 2011.

This project is funded in part by a Humanities New York CARES Grant with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the federal CARES Act. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this oral history does not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Special thanks to Helena Shaskevich, Charlotte Strange, Andrew Gurian, and Michael Blair.

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), one of the world’s leading resources for video and media art. As we celebrate this milestone, EAI will present a rotating series of video features from across our collection and publish a series of oral histories with key figures. To keep up to date on our anniversary activities, please sign up for our e-mail mailing list.